When a patient in the ICU needs a life-saving injection and the vial isn’t there, it’s not just a logistics problem-it’s a crisis. Hospital pharmacies are the frontline in the U.S. drug shortage epidemic, and injectable medications are the hardest hit. While retail pharmacies might run low on a painkiller or antibiotic now and then, hospitals face daily decisions that can delay surgeries, compromise cancer treatments, or force nurses to use less effective alternatives. And it’s getting worse.

Why Injectables Are the First to Go Missing

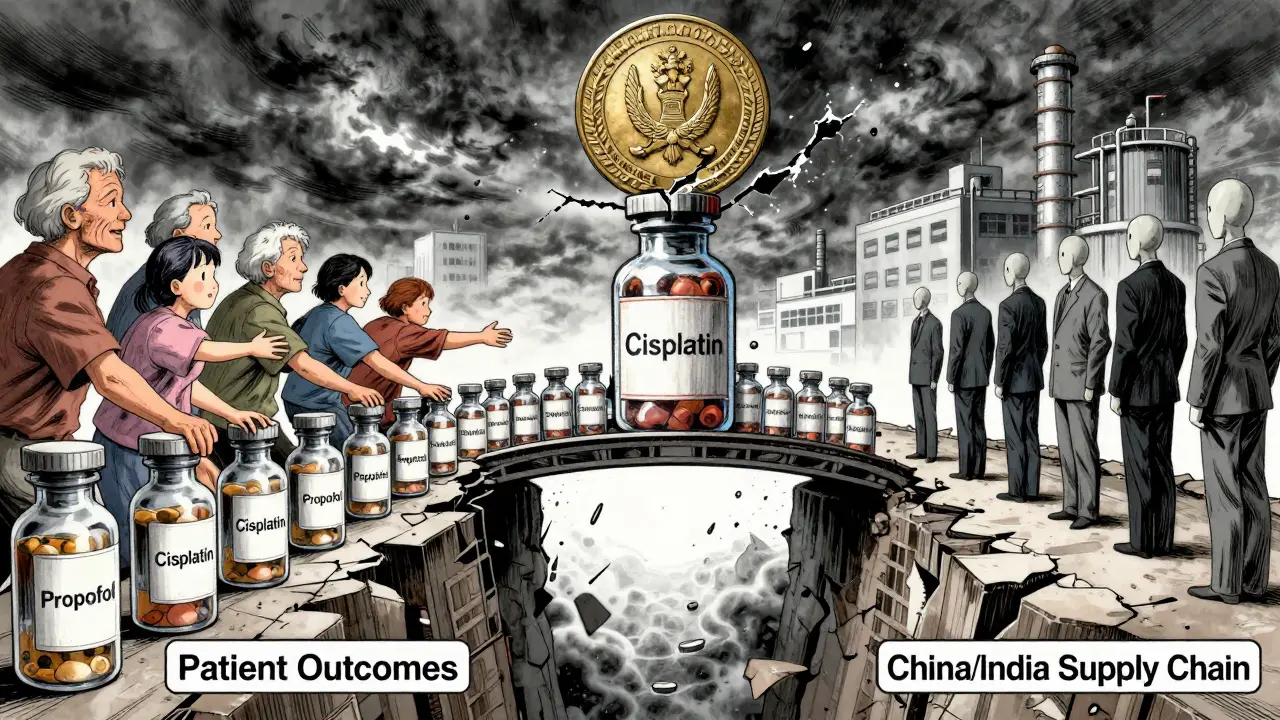

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to supply chain vulnerability. Sterile injectables-medications delivered directly into the bloodstream-make up about 60% of all active drug shortages. Why? Because they’re complex to make. Unlike pills, which can be mass-produced in automated factories, injectables require clean rooms, sterile environments, and precise temperature controls. One tiny contamination can shut down an entire production line. And when that happens, there’s no backup. The problem isn’t just about making the drug-it’s about making it profitably. Most injectable medications are generics, sold for pennies per dose. Manufacturers operate on margins of just 3-5%. When a factory in India gets shut down by an FDA inspection, or a tornado destroys a plant in North Carolina, companies don’t have the financial cushion to quickly restart production. The result? Months, sometimes years, without critical drugs like normal saline, epinephrine, or chemotherapy agents like cisplatin.Who Gets Hurt the Most

It’s not just hospitals that feel the pinch-it’s the patients. About 30% of people affected by drug shortages are between 65 and 85. These are the patients in intensive care, undergoing chemotherapy, or recovering from major surgery. They don’t have the luxury of waiting for a refill. A shortage of anesthetic drugs means elective surgeries get postponed. A lack of vasopressors can turn a stable cardiac patient into a code blue. And when nurses have to substitute a less effective drug because the right one isn’t available, outcomes suffer. Academic medical centers report being hit two and a half times harder than community hospitals. Why? Because they treat the sickest patients-those who need rare, specialized injectables. A hospital in Boston reported postponing 37 surgeries in just three months due to anesthetic shortages. In another case, a pediatric oncology unit had to switch from a standard chemotherapy cocktail to a less effective one because the preferred drug was unavailable for over eight months.The Supply Chain Is Fragile-and Concentrated

Eighty percent of the active ingredients for generic injectables come from just two countries: China and India. That means a single political dispute, a flood, or a regulatory crackdown can ripple across the entire U.S. supply chain. In 2024, a quality issue at a single Indian facility took cisplatin-essential for treating testicular and ovarian cancer-off the market nationwide. There was no alternative. No backup supplier. Just patients waiting. Even worse, the market is consolidated. Three manufacturers control 65% of the supply for basic fluids like sodium chloride and potassium chloride. That’s not competition-it’s a single point of failure. If one of them shuts down, the entire country feels it. And when a shortage hits, hospitals can’t just order more from Amazon. There are no wholesalers with extra stock. No quick fixes.

How Hospitals Are Trying to Cope

Hospital pharmacists are now full-time detectives, negotiators, and crisis managers. On average, they spend nearly 12 hours a week tracking down alternatives, approving substitutions, and coordinating with other hospitals to share limited stock. One pharmacist in Michigan told a colleague, “I spent three weeks calling every pharmacy in three states just to get enough normal saline to keep IV lines open.” Many hospitals have formed shortage management committees, but only a third feel they have the staff or authority to handle the scale of the problem. Some are creating tiered allocation systems-prioritizing the sickest patients first. Others are rewriting standing orders to allow safer, approved alternatives. But even these workarounds come with risks. Therapeutic substitutions can lead to errors, especially when staff are tired and under pressure. One study found that 42% of hospital pharmacists have had to use a less effective drug because there was no other option-and that directly impacted patient outcomes.Why Policy Hasn’t Fixed It

The government knows this is a problem. The FDA has been tracking shortages since 2001. Congress passed laws requiring earlier notifications. The Biden administration pledged $1.2 billion to bring drug manufacturing back to the U.S. But progress is slow. Only 14% of shortage notifications lead to timely resolution. The FDA can’t force companies to produce more. It can’t fine them for letting a plant sit idle. And while the Drug Supply Chain Security Act improves tracking, it doesn’t prevent shortages-it just tells you when they’re coming. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 was supposed to help. But a government audit found it reduced shortage duration by only 7%. Meanwhile, only 12% of injectable manufacturers use newer technologies like continuous manufacturing-which could make production faster and more resilient. The rest are still using 1980s-era equipment, running at full capacity, with no room for error.

The Future Looks Grim-Unless Something Changes

As of July 2025, there were still 226 active drug shortages in the U.S.-down slightly from earlier in the year, but still far above historical averages. Experts predict this won’t improve until at least 2027. The same forces that caused the problem are still in place: low profits, global supply chains, aging infrastructure, and no real consequences for manufacturers who let critical drugs disappear. Hospital pharmacies aren’t asking for more money. They’re asking for stability. For backup suppliers. For incentives to modernize. For a system that doesn’t treat life-saving injections like disposable commodities. Right now, the system is broken. And the people paying the price aren’t CEOs or shareholders-they’re the elderly, the critically ill, and the nurses who have to tell a patient, “We’re sorry, we don’t have the medicine you need.”What Can Be Done?

There are no easy fixes, but there are steps that could make a difference:- Financial incentives for manufacturers to maintain buffer stock and invest in modern equipment.

- Multiple approved suppliers for every critical injectable-not just one or two.

- Government-backed manufacturing hubs that can step in during emergencies, like a national drug reserve for sterile products.

- Real-time national tracking of inventory levels across hospitals, so shortages can be redistributed before they become crises.

- Strict penalties for companies that fail to report supply issues or shut down production without cause.

Why are injectable drugs more likely to be in shortage than pills?

Injectable drugs require sterile manufacturing environments, complex equipment, and strict quality controls. A single contamination can halt production for months. Unlike pills, which can be made in large batches with minimal oversight, injectables need clean rooms, aseptic processing, and frequent inspections. They also have very low profit margins, so manufacturers have little incentive to invest in backup capacity or modern equipment.

Which drugs are most commonly in shortage right now?

As of mid-2025, the most affected categories are anesthetics (87% shortage rate), chemotherapeutics (76%), and cardiovascular injectables (68%). Commonly missing drugs include normal saline, epinephrine, propofol, cisplatin, and sodium bicarbonate. Even basic fluids like IV hydration solutions have been in short supply for months at a time.

How do shortages affect patient care?

Shortages lead to delayed surgeries, postponed cancer treatments, and the use of less effective or riskier alternatives. One study found that 78% of hospital pharmacists reported direct treatment delays for critically ill patients in the past year. Nurses have reported having to use oral hydration instead of IV fluids, or substitute cheaper drugs that require higher doses and carry more side effects.

Why can’t hospitals just order more from distributors?

Distributors don’t hold extra stock of generic injectables because there’s no profit in it. Manufacturers produce just enough to meet demand-and when demand spikes or production stops, there’s no reserve. Unlike retail pharmacies, which can order from multiple wholesalers, hospitals rely on a narrow network of suppliers. When those suppliers run out, hospitals have nowhere else to turn.

Is this problem getting better?

No. While the number of active shortages dropped slightly from 270 to 226 between April and July 2025, the underlying causes haven’t changed. Most shortages (89%) are carryovers from previous years. Experts predict shortages will stay at current levels through 2027. Without major policy changes-like financial incentives for manufacturers or national stockpiles-the problem will only get worse.

Sonal Guha January 13, 2026

Injectables are a supply chain nightmare because they’re made in single-point factories with zero redundancy

One FDA citation in India and the whole US runs out of cisplatin

No buffer stock no backup no mercy

gary ysturiz January 13, 2026

This is heartbreaking but not surprising

Hospitals are doing heroic work with no support

We need to treat life saving meds like infrastructure not commodities

Fix this now before someone dies because we were too cheap to act

Jessica Bnouzalim January 14, 2026

Okay but have you seen the prices on these drugs??

Like… why is normal saline so expensive to make??

It’s just salt and water!!

And yet we have nurses crying because they can’t get enough for IVs

Someone’s making money somewhere… and it’s not the hospitals

And why are we still using 1980s equipment??

It’s 2025!!

We have drones that deliver pizza… but we can’t make IV fluid reliably??

This is insane

Lelia Battle January 16, 2026

The systemic failure here reflects a deeper cultural prioritization

We have optimized for cost efficiency over resilience

But when the cost is measured in human lives, efficiency becomes a moral failure

The notion that profit margins should dictate access to life-sustaining medicine is not economic-it is ethically indefensible

There is no market solution to a public health crisis

Only collective will can restore dignity to the process

And that will must be enforced, not requested

Rinky Tandon January 18, 2026

China and India are the problem

They control 80% of the active ingredients

And they don’t care about American patients

Why are we letting them hold our healthcare hostage

We need to ban imports from those countries

Make everything in the USA

Or else we’re just asking for more suffering

It’s not a shortage-it’s a betrayal

Ben Kono January 19, 2026

My aunt had her chemo delayed for six weeks because cisplatin was gone

She’s fine now

But she shouldn’t have had to wait

Konika Choudhury January 20, 2026

India makes the best generic drugs in the world

Stop blaming them

The real problem is US manufacturers who won’t invest

They’d rather pay fines than upgrade

And the FDA lets them get away with it

Darryl Perry January 21, 2026

The FDA has no enforcement power

That’s the root issue

Companies break the rules

Nothing happens

Fix that

Windie Wilson January 22, 2026

So let me get this straight

We’re relying on a single factory in India to keep cancer patients alive

And we’re proud of our free market?

Wow

What a system

It’s like having one lightbulb in your house and calling it energy independence