Ever bought a snack just because everyone else was eating it? Or picked a brand because your friends swore by it-even though you didn’t really need it? That’s not just coincidence. It’s social influence at work. And it’s shaping your choices more than you realize.

We like to think we make decisions based on logic, price, or personal preference. But research shows something deeper is going on. When we’re around peers-friends, classmates, coworkers-our brains start to rewire how we value things. Not because we’re weak, but because we’re human. We’re wired to fit in, to be accepted, to avoid standing out in ways that might cost us belonging.

Why Your Friends’ Opinions Change What You Choose

It started in the 1950s with Solomon Asch’s famous line experiments. Participants were shown three lines and asked which one matched a target line. Everyone else in the room-actors-gave the wrong answer. And 76% of the real participants went along with the group at least once, even when the answer was obviously wrong. That’s not stupidity. That’s the power of social pressure.

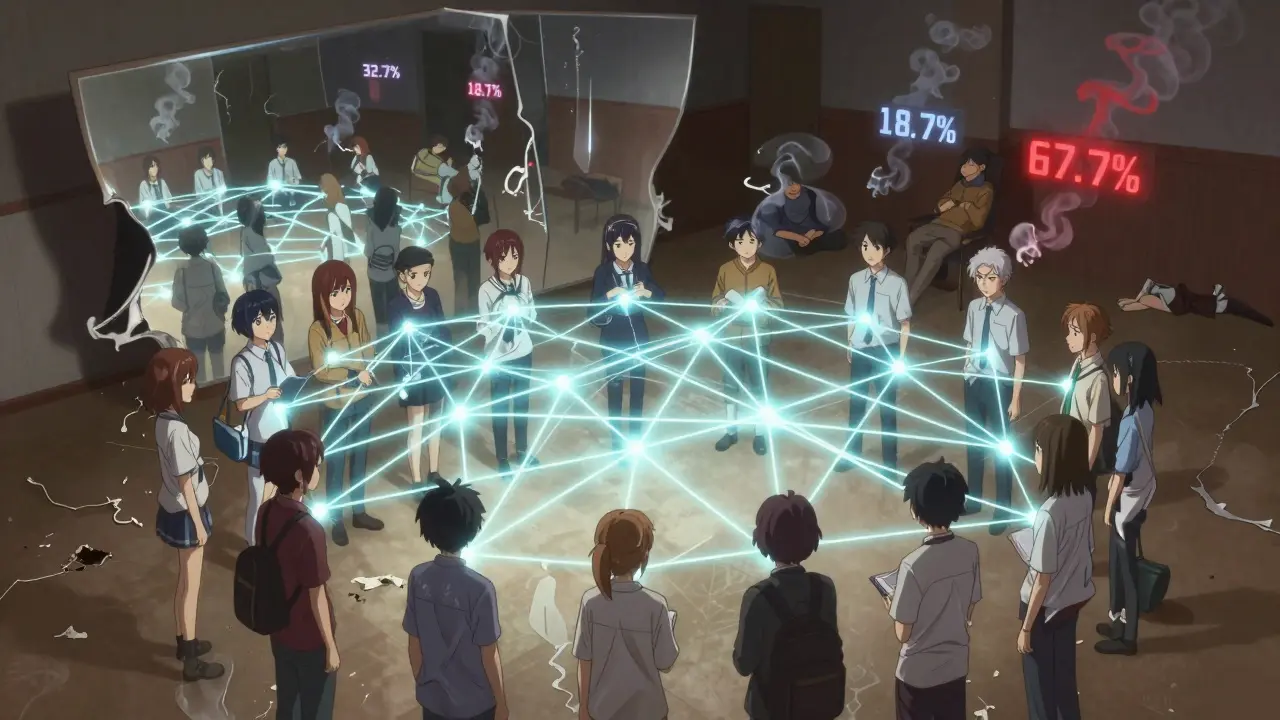

Today, we see the same thing-but in subtler ways. You don’t need someone telling you what to buy. You just need to see your peers doing it. A 2022 Princeton study found that when people conform to peer opinions, the brain’s reward centers-the ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex-light up 32.7% more than when they make independent choices. In other words, agreeing with your group doesn’t just feel safe. It feels good.

This isn’t just about fashion or gadgets. It’s about food, exercise, sleep, even how you handle stress. If your circle talks about intermittent fasting, you’re more likely to try it-even if you’ve never read a study on it. If your coworkers all take the stairs, you start taking them too. These aren’t conscious decisions. They’re automatic adjustments based on what you observe.

The Two Needs Driving Conformity

Not all social influence is the same. Research from the 2022 PMC study breaks it down into two core drives:

- Being liked (34.7% of conformity): You change your behavior because you want others to think well of you.

- Belonging (29.8% of conformity): You change because you want to feel like you’re part of the group.

These aren’t just feelings-they’re survival instincts. For most of human history, being kicked out of your group meant death. So your brain still treats social rejection like a physical threat. That’s why even small acts of non-conformity-like refusing to laugh at a joke everyone else finds funny-can trigger anxiety.

And here’s the twist: you don’t even need to know the people well. Studies show that people often conform to “generic, unspecified popular peers”-people they don’t personally know but assume are the norm. That’s why social media is so powerful. You see a thousand people using a product, and suddenly, it feels like everyone does.

Status Matters More Than You Think

Not all peers are equal. Influence isn’t random. It’s strongest when the person has higher status in your group.

A 2015 study in simulated chat rooms found that when a high-status peer endorsed a behavior, others were 37.8% more likely to follow-compared to just 18.2% when the same behavior came from someone with equal status. It doesn’t matter if the high-status person is the captain of the team, the most popular kid, or the CEO of the company. Their opinion carries weight.

But here’s the catch: influence peaks at moderate status gaps. If someone is way too far above you-say, a celebrity-you’re less likely to copy them. Too close, and they don’t seem like a leader. The sweet spot? Someone you admire but still feel connected to. That’s why school-based health campaigns work best when they use older students as peer leaders-not adults or strangers.

How Social Networks Amplify (or Block) Influence

Think of your social circle like a web. Some people are at the center. Others are on the edges. The structure of that web determines how fast ideas spread.

Networks with high density-where most people know each other-move opinions quickly. In dense groups, one person’s behavior can ripple through the whole group in weeks. But in loose networks, where people are isolated, influence stalls.

That’s why interventions like the CDC’s “Friends for Life” program reduced adolescent vaping by 18.7%-but only in schools where peer networks were tight. They didn’t just hand out flyers. They trained popular students to model healthy behaviors. And it worked because those students were already trusted, visible, and connected.

On the flip side, if your group is fragmented-say, you’re in a school where kids are split into cliques-trying to change behavior through peer influence fails. You can’t spread a message if there’s no path for it to travel.

What You Think vs. What’s Actually Happening

Here’s one of the biggest traps: you think everyone else is doing more than you are.

Studies show people consistently overestimate peer behavior. In one survey, 67.3% of teens thought their classmates drank alcohol more than they actually did. Another found people believed their peers used vaping devices 20% more often than the real numbers showed.

This is called pluralistic ignorance. It’s when everyone privately disagrees with a norm but publicly goes along with it-because they assume everyone else agrees. That’s why “everyone’s doing it” is often a myth. But the myth still drives behavior.

That’s why the most effective campaigns don’t just push healthy choices. They correct misperceptions. “Most students here don’t vape” is more powerful than “Don’t vape.”

When Social Influence Helps-Not Hurts

People talk about peer pressure like it’s always bad. But it’s not. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it depends on how it’s used.

Longitudinal studies tracking 1,245 Dutch teens over two years found that conforming to peers who studied hard improved academic performance by 0.35 standard deviations. That’s like going from a C to a B+ average. Meanwhile, conforming to peers who used drugs increased substance use by 0.28 SD.

The difference? The behavior being modeled. If your friends are reading, volunteering, or saving money-you’ll likely do more of it too. If they’re skipping class or staying up all night-you’ll probably follow that path.

This isn’t about being a sheep. It’s about being socially smart. Your environment shapes your habits more than your willpower ever will. That’s why changing your social circle can be more effective than any diet plan or productivity app.

How to Use This Knowledge-Without Being Manipulated

So what can you do with this?

First, be aware. When you make a choice, ask: “Am I doing this because I want to, or because I think others expect it?” You don’t have to reject peer influence. Just notice it.

Second, curate your environment. If you want to eat better, spend more time with people who cook at home. If you want to be more active, join a walking group. Your habits will shift without you even trying.

Third, be a positive influence. You don’t need to be loud or perfect. Just show up consistently. If you’re the person who brings fruit to meetings, who takes the stairs, who says “no thanks” to junk food-others will notice. And they’ll follow.

And finally, don’t fall for the myth that everyone else has it figured out. Most people are just guessing too. The real power isn’t in following the crowd. It’s in knowing when to step back-and when to step forward.

What’s Next for Social Influence Research

The field is moving fast. AI is now predicting who’s most likely to change their behavior based on their social media patterns-with 83.7% accuracy. Companies are selling “influence-as-a-service” tools to advertisers, raising serious ethical questions.

But the core truth hasn’t changed: we’re social creatures. We don’t make choices in a vacuum. We make them in relation to others. Understanding that isn’t about manipulation. It’s about freedom. When you see the invisible forces shaping your choices, you can finally choose-on your own terms.

Why do I care so much about what my friends think?

Your brain is wired to care. For most of human history, being accepted by your group meant survival. Today, that same instinct drives you to align with peers-even in small ways like clothing, music, or food choices. It’s not weakness. It’s biology. Studies show that conformity activates reward centers in the brain, making it feel good to fit in.

Can peer influence be used for good?

Absolutely. Programs like the CDC’s “Friends for Life” reduced teen vaping by nearly 20% by training popular students to model healthy behavior. When peers who are respected and trusted promote positive habits-like studying, exercising, or eating well-others follow. Influence isn’t inherently bad. It’s the behavior being modeled that determines the outcome.

Is peer pressure stronger in teens?

Yes, but not because teens are “easier to influence.” Their brains are still developing, especially the prefrontal cortex-the part that handles long-term thinking and resistance to pressure. Plus, social belonging becomes extra important during adolescence. That’s why peer influence peaks between ages 13 and 17. But adults are still affected. You just notice it less because you’re better at hiding it.

Why do I feel anxious when I disagree with my group?

Because your brain treats social rejection like physical danger. Neuroimaging studies show that resisting a unanimous group opinion activates the amygdala and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex-areas linked to fear and conflict. That’s why saying “no” in front of everyone feels so hard. It’s not just awkward. It’s physiologically stressful.

How can I reduce negative peer influence?

Start by noticing when you’re acting out of habit, not choice. Then, adjust your environment. Spend more time with people who model the behaviors you want. Limit exposure to groups that reinforce habits you’re trying to change. You don’t need to cut ties-just create space. Small shifts in your social circle can lead to big changes in your behavior over time.

Do social media platforms exploit peer influence?

Yes. Platforms use algorithms to show you content that matches what your friends like, creating echo chambers that reinforce beliefs and behaviors. Facebook’s own “Positive Community” initiative used peer modeling to reduce harmful content sharing by 19.3%. But many companies sell “influence-as-a-service” tools that manipulate users for profit. Awareness is your best defense.

If you want to change a habit-whether it’s eating better, sleeping more, or cutting back on screen time-don’t just focus on willpower. Look at your circle. Who are the people around you? What are they doing? Because chances are, your next big change won’t come from a new app or diet plan. It’ll come from the people you spend time with.

Joie Cregin January 15, 2026

OMG yes. I once bought matching hoodies with my coworkers just because they all did it. I didn’t even like the color. But it felt like a tribe thing? Like we were all in some secret club of slightly overpriced cotton. Now I laugh about it. But also... I still wear that hoodie. 🤷♀️

Melodie Lesesne January 16, 2026

This hit me right in the soul. I started taking the stairs after my office buddy did it for a week. Now I do it without thinking. No one even noticed. But I feel like a badass. 😌

Corey Sawchuk January 18, 2026

Been thinking about this a lot lately. I stopped buying trendy protein bars because my gym crew was obsessed. Turned out I just liked the taste. But I kept buying them for months just to fit in. Weird how that works

Stephen Tulloch January 19, 2026

LMAO so you're telling me humans are just glorified sheep with Wi-Fi? 🤦♂️ Of course your brain lights up when you conform-it's literally a dopamine trap designed by evolution to keep you from getting eaten by wolves. Now it's TikTok trends and $200 sneakers. We're not evolved. We're just better at hiding the herd mentality. 🐑📱

Rob Deneke January 21, 2026

You guys are overthinking this. Just be the person who shows up. If you bring fruit to meetings, someone will start doing it too. No grand plan needed. Small actions ripple. I’ve seen it happen. Just keep showing up

evelyn wellding January 21, 2026

THIS. I started walking after my neighbor did it every morning. Now I’ve lost 15 lbs and made 3 new friends. It wasn’t the diet. It was the people. 🙌

Chelsea Harton January 23, 2026

we are all just apes with smartphones lol

Corey Chrisinger January 24, 2026

It’s not conformity-it’s collective intelligence. Our ancestors didn’t survive by being lone wolves. They survived because they synchronized. The brain isn’t weak for liking belonging-it’s wise. The danger isn’t fitting in. It’s assuming your group’s norms are truth. That’s when you stop thinking. And that’s when the algorithms win.

So yeah. Be part of the herd. But keep your eyes open. The real power isn’t in following-it’s in noticing you’re following.

Christina Bilotti January 25, 2026

Oh wow. A whole essay on how people are easily manipulated? Groundbreaking. I’m sure no one ever noticed that teenagers care about what their friends think. Maybe next you’ll reveal that water is wet. 🙄

Also, ‘influence-as-a-service’? That’s not a thing-it’s just marketing. And you call this research? Please. I’ve seen better insights in a Target loyalty email.