When a drug has a narrow therapeutic index, even a tiny change in dosage can mean the difference between healing and harm. For drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin, a 10% shift in blood levels might trigger a seizure, a dangerous bleed, or organ toxicity. That’s why the FDA doesn’t treat them like regular generics. The rules for proving they work the same as the brand-name version are far stricter - and for good reason.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

A narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug is one where the gap between a safe dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. The FDA defines it mathematically: if the ratio of the minimum toxic dose to the minimum effective dose is 3 or less, it’s an NTI drug. That’s not a guess - it’s based on data from 13 drugs studied in 2022. Ten of them had a therapeutic index of 3 or lower. Three hovered just above it, but still got flagged because of how sensitive their effects are.

These aren’t just theoretical risks. Take digoxin. A blood level of 0.5 ng/mL might control heart rhythm. At 2.0 ng/mL, it can cause fatal arrhythmias. That’s a fourfold difference - and patients need to stay within that tiny window. The same goes for carbamazepine, lithium, and tacrolimus. One pill too much, one pill too little - and things go wrong fast.

The FDA doesn’t publish a public list of NTI drugs. Instead, they’re identified through product-specific guidance documents. If you’re a pharmacist or prescriber, you check the FDA’s guidance for that specific drug. If it’s labeled as NTI, the rules change.

How Bioequivalence Standards Differ for NTI Drugs

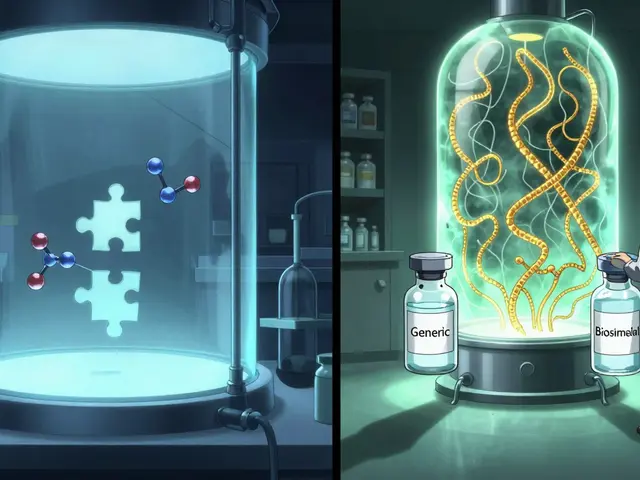

For most generic drugs, the FDA says: if the generic delivers 80% to 125% of the brand’s blood concentration, it’s considered equivalent. That’s called average bioequivalence (ABE). It works fine for drugs where a 25% difference won’t hurt.

But for NTI drugs? That’s not safe. So the FDA tightened the rules. Now, the acceptable range for bioequivalence is 90% to 111.11% - roughly half the tolerance. That means the generic must deliver nearly the same amount of drug, every time, in every patient.

It’s not just about the average. The FDA also looks at variability. For NTI drugs, they require replicate studies - meaning each patient takes both the brand and generic multiple times. This lets them measure how consistent the drug is from dose to dose. If the generic’s levels swing wildly compared to the brand, it fails, even if the average looks good.

There’s another layer: the upper limit of the confidence interval for the ratio of within-subject variability (test vs. reference) must be ≤ 2.5. In plain terms, the generic can’t be more unpredictable than the brand. If the brand is stable, the generic must be just as stable.

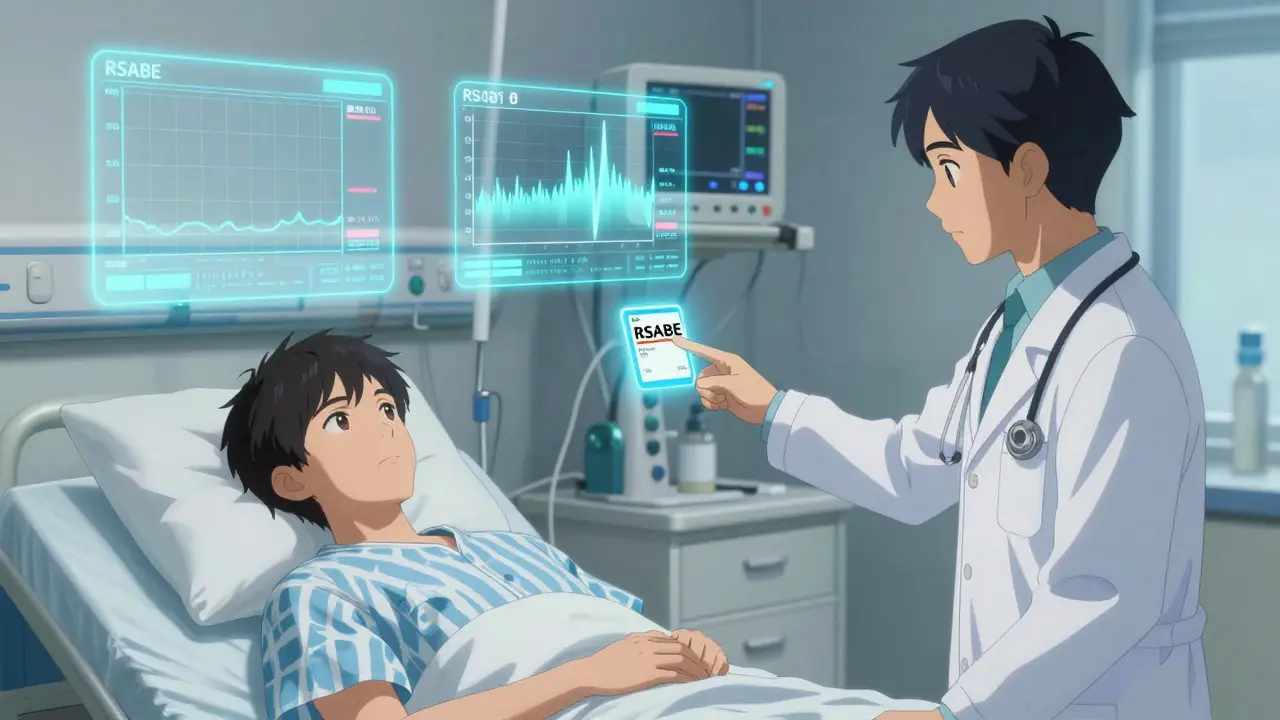

This approach is called Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE). It’s more complex than the old 80-125% rule, but it’s designed to catch drugs that might look equivalent on paper but behave differently in real patients.

Quality Control Is Tighter Too

It’s not just about what’s in the bloodstream. The FDA also demands tighter control over the manufacturing process. For non-NTI generics, the active ingredient can vary between 90% and 110% of the labeled amount. For NTI drugs? That range shrinks to 95% to 105%.

Why? Because if the pill itself has inconsistent potency - say, one tablet has 98% of the drug and the next has 104% - that’s a 6% swing. Multiply that across a patient’s daily dose, and you’re pushing them toward the edge of toxicity. That’s unacceptable for drugs like warfarin, where a 10% change can require emergency intervention.

Manufacturers of NTI generics must prove they can consistently hit that 95-105% target. That means tighter control over raw materials, more frequent testing, and better process validation. It’s more expensive. It’s more time-consuming. But it’s necessary.

Why This Matters for Patients

Patients on NTI drugs often rely on generics to save money. But switching between different generic versions - even if each one meets FDA standards - can be risky. Studies have shown that two generics that both pass the 90-111% bioequivalence test can still differ from each other in how they’re absorbed.

One study found that generic tacrolimus products from different manufacturers were bioequivalent to the brand - but not always to each other. That’s not a failure of the system. It’s a reminder that bioequivalence is about matching the brand, not each other. But for patients who switch between generics, that can mean unpredictable blood levels.

That’s why some states still require explicit patient consent before substituting an NTI generic. Some doctors avoid switching altogether. The FDA says real-world data shows generic NTI drugs are safe and effective - and they are, when used correctly. But the system isn’t perfect. And patients deserve to know why.

How the FDA’s Approach Compares Globally

The U.S. isn’t alone in worrying about NTI drugs. But the FDA’s method is unique. Health Canada and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) tend to use a fixed, narrower range - like 90-110% - for all NTI drugs, regardless of how variable the brand product is.

The FDA’s scaled approach is more flexible. It adjusts the limits based on how much the brand drug’s levels vary from person to person. If the brand is highly variable, the generic can have a slightly wider range. If the brand is rock-solid, the generic must match it exactly.

This makes the FDA’s system more scientifically precise - but also more complex. It requires more data, more statistical analysis, and more regulatory review. Other agencies are watching. Harmonizing global standards is a priority for the FDA, but it’s not easy.

Drugs That Fall Under NTI Rules

Here are some of the most common NTI drugs the FDA tracks:

- Carbamazepine (used for seizures and nerve pain)

- Phenytoin (another antiseizure drug)

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Digoxin (heart medication)

- Valproic acid (mood stabilizer)

- Tacrolimus, cyclosporine, sirolimus (immunosuppressants after transplants)

- Lithium carbonate (for bipolar disorder)

These aren’t just random drugs. They’re all used in chronic, life-critical conditions. Missing a dose or taking too much can lead to hospitalization - or death.

What’s Next for NTI Drug Regulation?

The FDA continues to refine its approach. In 2022, they formalized the therapeutic index ≤ 3 cutoff using pharmacometric modeling. That means fewer subjective judgments and more data-driven decisions.

They’re also pushing for more transparency. Product-specific guidances now clearly state the exact bioequivalence requirements for each NTI drug. That helps manufacturers design better studies and helps clinicians understand what’s been proven.

But challenges remain. Educating pharmacists and patients is still a hurdle. Many don’t realize that an NTI drug isn’t just another generic. Some states still block automatic substitution. The FDA wants to change that - but only if patients are informed and monitored.

Research is ongoing. Studies are tracking patients on generic tacrolimus and warfarin over years to see if outcomes match the brand. Early results are encouraging. But the goal isn’t just to approve generics - it’s to ensure that every patient, no matter where they live or which generic they get, gets the same safe, effective treatment.

Are all generic drugs held to the same bioequivalence standards?

No. Most generics must show they deliver 80% to 125% of the brand’s blood concentration. But for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, the range is much tighter: 90% to 111.11%. This is because even small differences in exposure can cause serious harm. The FDA also requires replicate studies and stricter manufacturing controls for NTI generics.

How does the FDA decide which drugs are NTI drugs?

The FDA uses a pharmacometric approach based on data. A drug is classified as NTI if its therapeutic index - the ratio of the minimum toxic dose to the minimum effective dose - is 3 or less. This cutoff was established in 2022 after analyzing 13 drugs. Drugs with high variability, low therapeutic margins, and the need for frequent blood monitoring are also flagged. The FDA doesn’t publish a public list; instead, NTI status is specified in product-specific guidance documents.

Can I safely switch between different generic versions of an NTI drug?

It’s not always safe. While each generic must meet FDA standards for bioequivalence to the brand-name drug, two different generics may not be bioequivalent to each other. Studies have shown this with drugs like tacrolimus. Switching between generics can lead to unpredictable blood levels. Patients on NTI drugs should consult their doctor before switching, and pharmacists should avoid automatic substitution unless the patient is closely monitored.

Why does the FDA use a scaled approach instead of a fixed range for NTI drugs?

The FDA’s scaled approach (RSABE) adjusts bioequivalence limits based on how much the brand-name drug’s levels vary from person to person. If the brand is highly variable, the generic can have slightly wider limits - as long as it’s no more variable. This is more scientifically accurate than using a fixed range like 90-110%. It ensures that the generic matches the brand’s real-world behavior, not just an arbitrary number.

Do other countries have the same NTI drug rules as the FDA?

No. Health Canada and the European Medicines Agency typically use fixed, narrower bioequivalence ranges (like 90-110%) for all NTI drugs, regardless of the brand’s variability. The FDA’s approach is more flexible and data-driven, adjusting limits based on the reference drug’s within-subject variability. This makes the FDA’s method more precise but also more complex. Global harmonization is a stated goal, but differences remain.

RAJAT KD January 9, 2026

NTI drugs are no joke. One wrong dose and you’re in the ER. Glad the FDA takes this seriously.

Jenci Spradlin January 10, 2026

man i used to work in pharma and let me tell you, the batch logs for warfarin generics were insane. every pill weighed to the milligram, and they’d throw out whole batches if one tablet was off by 0.5%. it’s wild how much work goes into something most people think is just "same pill, cheaper".

Elisha Muwanga January 11, 2026

Why does the FDA need to be so complicated? Other countries use a simple 90-110% rule and they’re fine. This over-engineering just drives up costs and delays generics. America thinks it’s smarter than everyone else.

Aron Veldhuizen January 12, 2026

Let’s be honest - this isn’t about patient safety. It’s about protecting Big Pharma’s monopoly. The FDA’s "RSABE" is just a fancy word for "make it harder for generics to compete." The data shows no meaningful difference in outcomes between generics that meet 80-125% vs. 90-111%. This is regulatory theater.

Matthew Maxwell January 13, 2026

It’s appalling how many pharmacists still substitute NTI generics without informing patients. This isn’t just negligence - it’s malpractice. The FDA’s guidelines are clear, yet enforcement is nonexistent. Someone needs to be held accountable.

tali murah January 14, 2026

Oh, so now the FDA is the hero? Let’s not pretend this is about science. They’ve been dragging their feet for decades. The first time a patient died because of a generic tacrolimus swap was in 2008. It took 14 years for them to finally tighten the rules. And even now, they still won’t publish a list. Classic bureaucratic cowardice.

Micheal Murdoch January 15, 2026

For anyone out there on lithium or warfarin - please, please don’t switch generics unless your doctor and pharmacist are on the same page. I’ve seen too many people get hospitalized because they got a "new" generic and their levels went haywire. It’s not about trust in the system - it’s about knowing your own body. Keep a log. Get your levels checked. Advocate for yourself. You’re worth it.

Jacob Paterson January 15, 2026

Wow, look at all this overthinking. So a pill has to be 95-105% potent? What’s next? Are we going to weigh the air molecules in the capsule? This isn’t medicine - it’s a cult of precision. If the drug works, stop micromanaging it. People are dying from opioid overdoses and you’re worried about a 3% variance in phenytoin? Priorities, people.

Jeffrey Hu January 17, 2026

RSABE is a statistical gimmick. The 90-111% range sounds precise, but it’s just a mathematical illusion. The real issue is batch-to-batch variability - which no bioequivalence study can fully capture. You need real-world pharmacovigilance, not lab numbers. Also, "95-105%" manufacturing? That’s impossible without HPLC on every tablet. Someone’s lying.

Diana Stoyanova January 18, 2026

Y’all are overcomplicating this. Think of it like baking a cake. If the recipe says 1 tsp of salt and you use 1.2 tsp - you ruin it. If you use 0.8 tsp - still ruined. NTI drugs are that cake. The brand is the original recipe. Generics? They gotta follow it exactly. No "close enough." No "it worked for me." Your life isn’t a beta test. And if you’re mad about the cost? Talk to your congressman, not the pharmacist.

Drew Pearlman January 18, 2026

It’s beautiful, honestly. The FDA didn’t just slap on a rule - they listened to the science, the patients, the data. It’s not perfect, but it’s the most thoughtful approach we’ve ever had. And yeah, it’s expensive. But saving someone from a seizure or a bleed? That’s priceless. Let’s not punish innovation because it’s hard. We’re talking about people’s lives here, not profit margins.

Chris Kauwe January 20, 2026

The FDA’s RSABE framework represents a paradigm shift in pharmacometric risk stratification. By anchoring bioequivalence thresholds to reference-scaled within-subject variability, they’re achieving a first-order approximation of therapeutic equivalence that traditional ABE models simply cannot capture. This is systems pharmacology in action - not regulatory overreach.

Lindsey Wellmann January 21, 2026

😭 I just got switched to a new generic for my warfarin last week… my INR went from 2.4 to 4.1 in 3 days. I had to go to the ER. My pharmacist didn’t even tell me it was a different maker. This isn’t science - it’s a gamble. #NTIDrugsAreNotRegularGenerics

Heather Wilson January 22, 2026

Let’s cut through the noise. The FDA’s approach is fundamentally flawed. If two generics are both bioequivalent to the brand, they should be bioequivalent to each other. The fact that they aren’t proves the entire system is broken. This isn’t precision - it’s chaos disguised as science.

Pooja Kumari January 23, 2026

I’ve been on tacrolimus for 12 years. I’ve switched generics 5 times. Each time, I felt different - dizzy, nauseous, like my body was screaming. No one listens. Doctors say "it’s within range." But range doesn’t feel like safety. Range doesn’t stop the panic attacks. Range doesn’t tell you why you’re crying for no reason. I’m tired of being a lab rat.